May 26, 2025

5/26/2025 | 55m 34sVideo has Closed Captions

Aviva Siegel; Sir Geoffrey Nice; Joni Levin & Keith Clarke; Hari w/John Vaillant

One year after her release, former Israeli hostage Aviva Siegel reflects on her experience and the fate of her husband still being held by Hamas. Sir Geoffrey Nice on the ICC’s decision to issue an arrest warrant for Israeli PM Netanyahu. Joni Levin and Keith Clarke on their new docuseries “Call Me Ted.” “Fire Weather” author John Vaillant on what the second Trump administration means for climate.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

May 26, 2025

5/26/2025 | 55m 34sVideo has Closed Captions

One year after her release, former Israeli hostage Aviva Siegel reflects on her experience and the fate of her husband still being held by Hamas. Sir Geoffrey Nice on the ICC’s decision to issue an arrest warrant for Israeli PM Netanyahu. Joni Levin and Keith Clarke on their new docuseries “Call Me Ted.” “Fire Weather” author John Vaillant on what the second Trump administration means for climate.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Amanpour and Company

Amanpour and Company is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Watch Amanpour and Company on PBS

PBS and WNET, in collaboration with CNN, launched Amanpour and Company in September 2018. The series features wide-ranging, in-depth conversations with global thought leaders and cultural influencers on issues impacting the world each day, from politics, business, technology and arts, to science and sports.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[MUSIC] >> Hello everyone and welcome to Amanpour & Company.

Here's what's coming up.

One year since a week-long ceasefire freed many of the Israeli hostages, the families of those still held in Gaza are calling for their release.

I speak to one of them.

As the world reacts to the ICC indicting the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, I speak to leading human rights lawyer Geoffrey Nice, the man who prosecuted the former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic.

Then- >> I was the first station ever to go, seven days a week, 24 hours a day.

And that was the future.

>> Ted Turner changed the media landscape forever when he founded CNN.

And at a time when journalists are under threat around the world, a new docu-series takes us back to where it all began.

My conversation with producer Joni Levin and director Keith Clarke.

Plus- >> We're actually having to almost redefine what seasons are.

>> As 2024 becomes the hottest year on record, Hari Sreenivasan sits down with John Vaillant, author of Fire Weather, to explore the rapidly changing relationship between us and the environment.

[MUSIC] >> Amanpour & Company is made possible by the Anderson Family Endowment, Jim Attwood and Leslie Williams, Candace King Weir, the Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Anti-Semitism, the Family Foundation of Leila and Mickey Straus, Mark J. Blechner, the Filomen M. D'Agostino Foundation, Seton J. Melvin, the Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, Charles Rosenblum, Koo and Patricia Yuen, committed to bridging cultural differences in our communities, Barbara Hope Zuckerberg, Jeffrey Katz and Beth Rogers, and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

>> Welcome to the program, everyone.

I'm Christiane Amanpour in London.

One of the wars on Israel's borders could be drawing to a close with a potential cease-fire deal with Hezbollah.

A source tells CNN the Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has approved an agreement in principle, but any deal would still need to be approved by the cabinet, which is planning to meet and vote on Tuesday.

Lebanese officials say dozens were killed in an Israeli strike over the weekend and that the death toll has risen to over 3,000 since mid-September.

Meantime, there is little hope for a cease-fire in Gaza, where the humanitarian situation in the north has been described as apocalyptic by aid officials.

It's been one year since the only deal between Israel and Hamas led to the release of over 100 captives taken on October 7th.

Around 100 hostages are still believed to be held inside Gaza to this day.

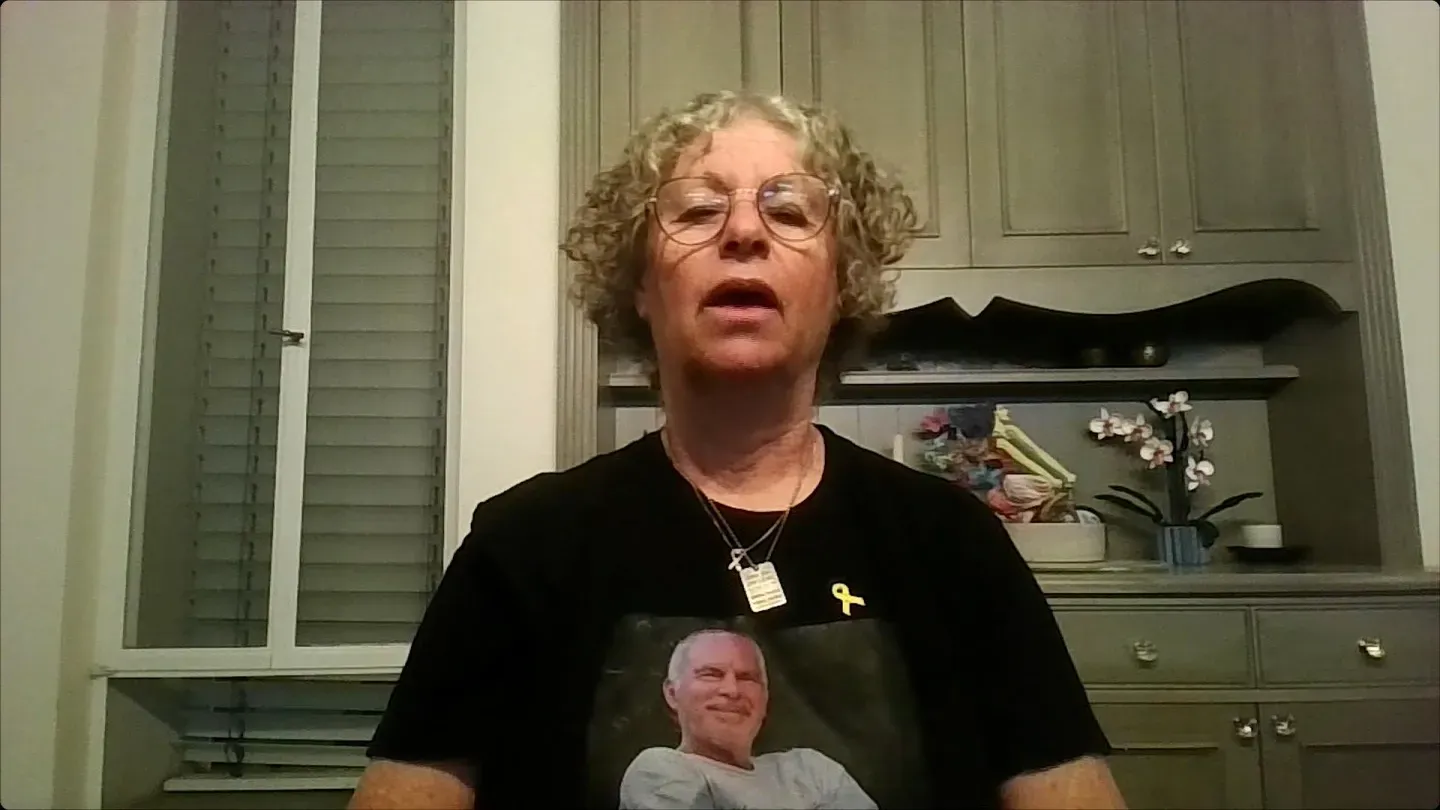

Aviva Siegel was released as part of that original deal last November, but her husband, Keith, an American Israeli citizen, remains in captivity, and she's joining us now from Israel.

Aviva Siegel, welcome to the program.

And I just want to know what you're thinking today regarding the fact that you and about 100 others were released exactly a year ago.

What do you think about that deal that enabled that?

Hello, everybody, and thank you for having me.

I am lucky to be sitting here and that everybody can see me alive because I nearly died in Gaza.

The only way to get the hostages out is to bring them back with a deal, and we know that.

After so many months and so many days have passed, while Keith, my husband, an American citizen, is underneath the ground, 40 metres underneath the ground, and just praying that somebody will come and take him out and bring him home.

I cannot wait for that to happen.

Aviva, do you know that he's under the ground?

Have you had word from others?

Were you kept underground?

What was your situation, and what do you think your husband is going through?

Yes, I was twice underneath the ground, and I want to tell everybody that it's worse than hell.

It's the worst thing that anybody can go through in this world.

We were just thrown underneath the ground 40 metres, and we were left there alone.

I remember there were two terrorists that were with us, and they were talking, and then suddenly it was silence, and I looked at Keith and I said, "Keith, do you think they left us here alone underneath the ground?"

It was dark.

We could hardly see anything, and we did not have any oxygen to breathe.

We got to a state that I looked at Keith and saw that he could hardly breathe, and he said that he feels that he can't breathe.

And I want to tell you that I told Keith, "Just lie down and try and breathe," and that's what we did.

We just lay down with no-- not able to even talk, to pick ourselves up, even to sit.

We had to lie down and try and breathe while I was thinking in my head, "Who is going to die first, Keith or I?"

And I just prayed that I would die first because it was very difficult for me to see Keith.

I could not even watch him and watch his chest going up and down and up and down while I felt the same.

I just want to die.

Have you heard any word about him from any of the other hostages or anybody?

No, not at all.

The only thing that we do know is that Keith-- they released-- the Hamas terrorists released a video of Keith in April, and that's more than a half a year ago.

Keith looks pale.

He looks old.

He looks tired.

He's begging and he's crying to get out of there.

He's 65 years old.

He was taken from his house with Hamas terrorists in his pajamas and he's still there underneath the ground.

We've been told that the hostages are underneath the ground just where I was and I nearly died.

Can I ask you, Aviva, since your release, you've been part of a hostage family advocate group.

You want them back, and this week hostage families gathered to mark the anniversary of that one deal that enabled your release and that of others.

The theme of the gathering was a year is too long for a deal.

So why do you think there hasn't been another deal and there haven't been hostages released in that fashion?

Well, I don't know why it's taking so long.

I just do know that Keith is not sitting in front of me and I'm waiting for him to come back, and I just want him to come back alive.

I want him to come back strong, and I am just so scared of what kind of Keith we're going to get back, how thin he's going to be, what is he going to look like, if he's going to be so ill that we'll just have to take care of him for the rest of his life because it's dangerous there.

The Hamas terrorists did not treat us like people.

They did everything they wanted to make us feel that we're not even human beings.

They've taken all human rights away.

We weren't allowed to talk.

We weren't allowed to hug.

We weren't allowed to feel.

We weren't allowed to stand or move our bodies.

And you know, Keith, while he was taken, he was pushed by the Hamas terrorists, and they broke his ribs, and they shot him on his hand, and he used to beg them to lie down sometimes during the day just to relax his pain, and they said no.

They used to eat in front of us while they starved us, and they used to drink water while they did not bring us any water to drink.

I'm a witness of one of the girls that was touched, and I just remember how fragile she was after it happened, but she had to continue to the Hamas terrorists that did touch her.

I'm a witness to one of the girls that was beaten up into pieces, and she was hit in such a brutal way, and she did not even scream because she was scared to.

She was scared that they would kill her, and I remember when she came back after they beat her, she was shaking and crying, and I could not even give her a hug.

I was not allowed to, and I'll never forget them treating Keith in such a brutal way, and so many times I wanted to just cry while I couldn't, but I used to look at Keith in his eyes and tell him that I love him and that I care about him because that's the only thing that they let me do, the Hamas terrorists.

They took control of us in any way that you can think of.

I'll never forget myself taking my foot out of a blanket because I was too hot to cool myself down, and the Hamas terrorists came and threatened me that I'm not allowed to take my foot out, and that's the amount of control that the Hamas terrorists had on us.

And one of the times they took us and they put black material and covered my eyes, and I had to walk myself down three stairs of stairs and trying to figure out where to put my next foot.

I'm 63 years old.

Keith is 65 years old.

He was taken by Hamas, and Hamas is responsible of everything that's going there, and Hamas is responsible of not bringing and letting Keith and all the hostages come home.

I'm worried.

I'm worried.

We hear you loud and clear, and obviously, like you, we really hope that Keith and the others come back, and we just hope that a ceasefire in Lebanon may mean a ceasefire in Gaza at some point, but we really, really appreciate you being with us on this anniversary of your release.

I can just imagine the horror and the pain that you're going through.

Thank you for being with us.

Thank you so much.

I just want to say that Keith and I are peacemakers, and we want good for the whole world, so please help us make this world a better world for everybody.

And that's a really strong message to end our conversation on.

Thank you for that.

Now, Israel's cabinet has voted to sanction Haaretz, which is the country's oldest newspaper.

That happened over the weekend.

Citing its coverage of the war on Gaza following the October 7th attacks, Haaretz described the move as an attempt to "silence a critical, independent newspaper."

Meantime, Israelis and many around the world are still digesting the ICC's decision last week to issue an arrest warrant for the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and from the deputy Hamas leader, Mohammed Deif.

The court said it found reasonable grounds to believe that Netanyahu bears criminal responsibility for war crimes, including starvation, as a method of war.

British Foreign Secretary David Lammy says the U.K. would follow due process if Netanyahu visited Britain, but the United States and other allies have rejected the ICC warrant.

Geoffrey Nice is a leading human rights lawyer who prosecuted the former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic at the U.N. War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague in 2002, and he joins me now from Canterbury here in England.

Welcome to the program, Geoffrey Nice.

You heard-- Let me just-- Let me just-- Let me just respond to Aviva Siegel.

You just heard this desperate commentary from a former hostage whose husband is still there and the description she made of how she was treated by Hamas and how the others were treated by Hamas.

I want to ask you your opinion as a legal scholar and one who's prosecuted these crimes before.

Do you think Hamas should have been charged with genocide as well as the crimes against humanity that they have been charged with?

At least three people, Sinwar, Haniyeh, who are both being killed by Israel, and Deif, who we don't know whether is alive or not, because genocide was not part of the charges.

- I have no fixed view on whether the evidence was sufficient to meet the strict test of genocide on one side or the other.

What is absolutely clear and has been clear from before this conflict or war started is that what Hamas has done, both in the firing of un-aimed rockets and particularly in respect of hostages, is of course criminal.

There's no doubt about its absolute wickedness, and indeed it would be very hard not to be moved by the extremely powerful statements of your previous contributor.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that Hamas is culpable of genocide because genocide requires proof of a particular state of mind of the leader or other person suspected of committing genocide.

And it's not easy to prove that state of mind, especially against leaders who don't say very much, as the leaders you refer to did not do.

- Just as a devil's advocate, you know that the charter talks about the elimination of the state of Israel.

Does that warrant, does that reach a legal definition?

- That, I think, has always been thought of as a possible or probable component part of any allegations of genocide made against those who cleave, stick to that particular charter.

I think there's been some variation of it, you'll be able to tell me if I'm wrong about that.

But that is not necessarily in itself sufficient.

Hamas may be regarded as wider than simply those who drafted the original charter.

So I'm afraid, or not afraid, I don't think that in itself is enough.

It may also be the case that the court in issuing these arrest warrants has in mind that it can add further charges, allegations, to the allegations that support arrest warrant or arrest warrants.

- All right.

So let me ask you now the bit that has caused a huge sort of, you know, hornet's nest, and that is the Thursday indictment of not only Mohammed Deif of Hamas, who was deputy of the military wing known as the Al-Qassam Brigades, but of Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel and his defense minister, Yoav Gallant.

And that is, you know, the thing is, alleged crimes against humanity were part of a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population of Gaza.

You know, back in May, you told me that you welcomed all the investigation and Karim Khan's decision to apply for warrants.

Now the warrants have been approved by the panel at the ICC.

But what I want to first ask you is, are you surprised by the level of rejection of these warrants against Israeli leaders by allies, you know, and many, many newspapers and leading opinion makers and thought leaders?

- No, I'm not surprised.

The horrifying conflict between Palestinians in Gaza, maybe elsewhere in Israel, and the state of Israel generates the strongest of emotions in politicians and in commentators and even in media.

And the legal issues of whether or not certain crimes may have been committed, and if so, by whom, need to be detached from emotion and looked at clinically.

So on the one hand, there's no reason to doubt that the very extended consideration given by these judges to the material presented to them has led to a solid conclusion that it may be very difficult to change on any form of appeal or reconsideration.

But it's not going to change the emotional response on both sides about this conflict.

And those, therefore, lead both to enthusiastic acceptance of the appropriateness of countries arresting Mr. Netanyahu, should he and Gallant and the other gentleman or man, if they fall into a particular country, and on the other side, to outright rejection of the work of the court.

It's unfortunate, in my view.

- Go ahead.

What's unfortunate?

- It's very unfortunate that there isn't a more general acceptance of the use of -- and I use the word "use" perhaps in a particular way -- the use of the court by the international community in big and powerful countries generally.

What we, the people, you and I, wish to see is the end of war.

We wish to see this kind of horrifying treatment of people on both sides come to an end.

And I'm afraid our political leaders overlook the potential value of investigation, not necessarily convictions by war criminals that may or may not affect the behavior of future leaders of conflicts.

We overlook, or they overlook, the value of investigation.

If support had been given to the ICC to investigate Operation Protective Edge, which happened in 2014 when it was given jurisdiction, if that had had enthusiastic support, it's by no means certain that what happened starting in October last year would have happened.

- Can I ask you, Jeffrey -- - Why?

- Yeah, I just got -- I don't have a huge amount of time left, but I want to ask you this.

I was, you know, at The Hague, reporting on your prosecution of Slobodan Milosevic and then, of course, all the other alleged war criminals who also were indicted on genocide charges.

And, of course, there were a whole load of their backers who totally rejected it -- Russia, the East European nations, the global South.

They totally rejected it.

The same has happened about the ICC indictment of Putin.

We know the ICC has indicted the former president of Sudan and others.

Do you -- This is the first time the leader of a democratic country supported by the United States has been indicted.

So, what do you make of that?

I mean, that's one of the fault lines that we're seeing right now.

- Well, standing back and not focusing on the horrors of this particular conflict, for the court to deliver on its mandate and to look at a problem that happens to be sensitive in the United States of America is a good thing because it shows that there is at least the possibility that the admittedly limited value that there may be in judicial investigation and processes of an international court can stand up to the big pressures that inevitably come from hegemonic powers like the United States of America.

And I suspect time will show that the majority of the populations around the world would prefer to see the international criminal law, in this case, doing what little it may but the best it can to seeing a conflict such as the horror happening in Israel, Gaza, and on the West Bank continue.

- And lastly, one of the statutes or one of the guidelines is that if the country has an independent and active judiciary, well, it should be left to the country to do it.

The ICC said that, you know, there'd be no progress since it applied for the warrants.

What do you make of that?

Do you think it was too short a time to give the Israeli judicial system a chance to look into it?

Could it have done in the midst of war?

- They were specifically invited to consider asking for a deferral.

They didn't.

That was one of the matters dealt with as a matter of jurisdiction.

Is it likely or possible in the particular and emotional circumstances in which this conflict sits that Israel would institute war crimes trials against Mr. Netanyahu?

I think it's unlikely.

- All right.

Sir Geoffrey Nice, Chief Prosecutor at the War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague against Milosevic, thank you so much indeed.

Now, he's the man who changed the media landscape forever.

When Ted Turner founded CNN in June 1980, the first ever 24-hour cable news channel, he democratized information by beaming it into homes all around the world.

Now, a new docu-series, "Call Me Ted," takes us back to where it all began with an intimate look at his personal life and his turbocharged career.

Here's a clip.

- I just came up with the idea that "Superstation" would be a good way to describe ourselves.

- How come no one else had thought of that?

- How come nobody else thought the world was round until Columbus came around?

- Ted was a legend, an American hero.

[upbeat music] - He wanted to build this entertainment empire.

- And I spoke to the husband and wife duo, producer Joni Levin and writer-director Keith Clark, about Ted Turner's guiding principles and his enduring legacy.

Joni Levin and Keith Clarke, welcome to the program.

A lot has been done on Ted Turner.

What was it that you wanted to achieve with this series?

- You know, I felt about seven years ago when I was thinking about Ted, I thought that nobody had really done that definitive deep dive on his life and legacy where it's not just his achievements, which are many, but it was really looking at the shadows and the obstacles that this man had to overcome to become the person that he is today.

And the thing that I loved about Ted is that he always felt that, you know, it was we the people, you know, the fans in the stadium, the citizens of the world that could change the momentum of a game, whether it's climate, whether it's nuclear, the environment, preservation of democracy, like he has done and continues to do.

And that was something that I felt that everybody should take a page from.

And it was being able to really put that forth, you know, so that people could take a look at this and become active, proactive, you know, be involved, believe in themselves.

He was such a believer.

He was told no so often, and he just took no and turned it into on.

I think that's such a great message.

And so that was really, you know, what I wanted to put forth and why I wanted to do this.

- Keith, do you think you guys learned anything more about Ted than you didn't know before by going through this process that Joni has described?

- Well, yeah, I think that, you know, what's interesting to me from a storyteller's point is just his personal journey.

You know, we can appreciate his accomplishments of many of the icons that we have out there, but Ted's journey, you know, when a man stands up and, you know, basically says at the beginning of our story, "I'm afraid of abandonment.

I'm afraid to be alone."

I just think that's such a deep dive into somebody's psyche and how they accomplish so much, and yet they're carrying this burden that basically just guided him each and every day.

- I want to take this opportunity to play one of the clips you've given us, and it is exactly about the idea of what happened, how he was abandoned at a very, very young age.

Here's this clip.

- I came along next November 19th, 1938, the first Turner born north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Another beautiful baby, Mary Jean, came along in September of 1941 and was the apple of my parents' eye.

[explosion] That date was significant because when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor just a few months later, my father joined the U.S. Navy.

They decided to take their infant daughter, Mary Jean, but leave me behind to attend the Cincinnati boarding school.

I was four years old.

- Honestly, just that scene is heartbreaking, and of course, you know, I've been an employee and an admirer of my boss for decades, and yet that vulnerability and the way you portrayed it is something not all people know about.

Tell me, Joni, what did that initial sense of abandonment do to him?

How did it affect him as a young man and then as an entrepreneur and a global game changer?

- Well, I think, you know, I think he struggled with that and anxiety a lot, but what it did is it also propelled him forward, and so it's almost like the idea that, you know, if you, as a shark, you know, if you don't keep moving, you die, and that's kind of Ted.

He always needed to be moving.

There was always more to do.

There was always more mountains to climb.

So I think on one hand, it was, you know, a powerful motivator for him, and yet it also was something that always damaged him.

You know, it's like Jane said, his father tried to break him, and he didn't, but I think his father really damaged him, and that was the beginning of the damage.

John Malone says this wonderful thing.

He said, "No man of success can pull the needle out of your ass that's been stuck up there since you were a child," and that was his needle.

- Let's just say right now from the outset, people like John Malone, Brian Roberts, these are also titans of this industry, and I think they both feel that they had a lot to owe Ted Turner, who was the, you know, the trailblazer, and as such, Keith, you got them as executive producers.

They helped fund, and they were very important interviews throughout the series, right?

- Ted, as we know, and as people will see, is a bigger-than-life character.

You know, he's a pirate.

He's all of those things, daring do, you know, sailor, champion, lust at sea, all of those great things, and the importance of that for these guys is they think they live vicariously through it.

They're more conservative guys.

They might do some of those things.

They don't do it to the extent, and they allowed this guy, you know, the classic mouth of the South, go forth and say all the things and, you know, bust down the doors, and I think that they all acknowledge, at least privately and a little publicly, I guess, is that they owe their fortunes to Ted.

You know, when cable started, they had a hope of getting something like 8% of the audience nationwide.

Ted came in and said, "Hell no, I want 100%.

You know, I want to compete with the networks."

- And also, just remind people, I mean, I know it because I work for CNN, but with that risk and that gamble and that all-in, he changed the entire media landscape.

It was really a global revolution.

Just remind how that happened and how perilous it was and how it could have failed at any moment along the way.

- Well, and that again goes back to, you know, Ted's nature, you know, his instinctive nature.

I mean, he really had it, you know, whatever that "it" is.

But, you know, again, people thought he was nuts, and they always said no to him, and as I said, he took no and turned it into on.

That was his--that was who he was, and so he was always planting the flag, you know, and he used to say, you know, "I'm just going to go as far as I can as fast as I can, and I'll worry about it when I get there," whether it was CNN or cable or, you know, whatever it was, and that was just his nature, and I think it's just his inner belief, his inner belief in who he was, and things were not always transactional for him.

It was really about doing the right thing, and you don't find that often.

- I was going to ask you that, 'cause that is something that, you know, those who work for him and have been in his orbit really admire, the fact that he always did the right thing on climate, on, you know, the environment, on nuclear weapons, you know, on even trying to bring peace between the Soviet Union, as it was, and the United States.

So I want to play the other clip that we have, and that is him narrating from a different project how essentially he took over his father's billboard business, and the idea was that he was trying to save that before even he became the cable revolutionary.

Here we go.

- Truth be told, I doubt that most people thought I was up to running the business anyway.

After all, it wasn't long before that that my father had declined on giving me even the top job in the Atlanta operation.

- He said, "Teddy, you're just not gonna make it."

- But it was, "I really want to show him, prove to him that I could do it."

For whatever reason, when his dad was around, he was always a failure.

- Turner Advertising represented my father's life's work.

He loved the company, and what he'd really want me to do was to save it.

- So again, it's a really interesting beginning for him business-wise.

So he's narrating part of that, and then you have his actual son, Teddy Jr., picking up some of the story.

So he always felt that he had to somehow please his dad, who was in his life very hard on him often, and who ended up dying by suicide, and that also was a big burden that Ted carried through his life.

- Yeah, I think that Ted was haunted by his father.

I think for Ted loved his father, even though his father abused him.

I mean, you know, he physically abused him, beat him, and all that stuff, which is what Joni says earlier.

As Jane said, you know, the father tried to break him but couldn't.

And it's also, I think, the sins of the father that had haunted Ted.

You know, it's all about choices at the end of the day, right?

And so his father was a womanizer, and, you know, that was Ted, too.

And, you know, his father wasn't around for his kids, for Ted, when he was young.

And Ted followed that, too.

That was the sins of the father.

But at some point or other, Ted had this fabulous revelation of what was important.

You know, he had three things in his life.

He had family, he had business, and he had sailing.

Sailing, he was, you know, named Sailor of the Year four times in a decade.

He won the America's Cup.

He had survived the Fastnet race, you know, when 15 other people died and 80 boats were sunk.

It's the worst disaster in history.

And Ted is at this crossroads.

He's starting CNN.

"What's most important to me?"

You know, and he looked around, and at one time he discarded his family and said, "You know, what's important to me is sailing and business."

And then he looked at this moment and said, "You know what?

"Family's more important.

"Business is important.

"I'm going to put down the other love of my life, sailing."

And he just quit.

Then he just focused on his family and business.

And then... And I think that's really the arc of his story.

I mean, he's not a righteous man.

He started off somewhat selfish, I would say, but then becomes more selfless when he does realize that it's not always about him.

It is what you have left at the end of the world.

It's the family, and it's the environment, and it's our planet, because he loves the planet.

He loves the people within the planet, and that's his whole goal, was to save.

-Yeah.

-And so at the end of the day, I think that's ultimately where he got to.

-And finally, Joanie, I want to ask you, 'cause we haven't really talked about the impact of CNN on the world.

And just what will the series tell about CNN, its original promise, how it exploded onto the world, obviously, during the first Gulf War, and where it stands now, given how legacy media is almost being overtaken by whatever, podcasts and social media and streaming?

-Yeah.

You know, when it first started, I mean, Ted always felt that it was not about the personalities.

It was about giving the facts.

Let's state the facts and let people decide how they feel about things.

And, you know, that was what he was all about and, you know, wanted to be international, wanted to be everywhere.

And that really started when he went and met with Castro.

And after he realized, you know, Castro really looks at CNN all the time.

He can't live without it.

That's when Ted came home and picked up the phone and started calling all these other countries to set it up.

But, you know, you were there at CNN early on when every week you were wondering whether he could even pay the bills.

And so for him, it was just -- I think it was the idea of connecting the world.

I mean, that was really, I think, his whole goal at the beginning, was making sure that, you know, we should all be connected in a sense.

-CNN changed the world, but I think CNN changed Ted.

-I dedicate the news channel for America.

-I think that's when he realized the world is bigger than his little world of Atlanta, his sailing, and all of these things.

When he went and started going out and meeting these -- the leaders of the world, they all wanted to meet Ted.

Because, obviously, the reach of CNN in itself is that they could -- everybody could tap into what the Americans were thinking, et cetera, et cetera.

But it changed Ted.

And that's when he says, "You know what?

The world is bigger than me.

I'm interested in the environment.

How can I use my platform to go out there?"

And the guy was a rock and roll star.

-Jonie Evans, Keith Clark, thank you so much.

And it is a remarkable story.

The six-part documentary "Call Me Ted" is now streaming on Max, which is owned by CNN parent company Warner Brothers Discovery.

Now, the annual climate summit wrapped up in Baku, Azerbaijan over the weekend after much wailing and gnashing of teeth over the amount rich, polluting nations should be paying poorer nations to decarbonize and mitigate their climate crises.

The deal struck was about a quarter of what they had asked for.

This COP 29 in oil-producing Azerbaijan follows last year's in the UAE, also a petro-state, but which hammered out a landmark commitment to transition away from fossil fuels.

But Saudi Arabia has been lobbying to derail that commitment ever since and hopes that Donald Trump's return to the White House will help, given his drill baby drill policies and his cabinet picks filled with industry execs and deregulators.

But as wildfires spread across North America with increasing frequency, the dissonance between that harsh reality and climate policy is being felt.

Author John Vaillant details this in his recent New York Times opinion piece, and he's joining Hari Sreenivasan in this discussion.

-Christiane, thanks.

John Valliant, thanks so much for joining us.

You know, Americans, and I guess North Americans in general, are used to seeing almost now a forest fire season, and we associate it with, say, California or maybe Colorado.

You wrote a piece in the New York Times recently that said, "Ladies and gentlemen, the Northeast is burning."

Why is this significant?

What's the change here?

-I think what we're seeing is this creeping of flammability, and like so many other Americans and Canadians, we assumed 10 years ago that wildfires were a California problem, maybe a Colorado problem, maybe an Australia problem.

But I live in British Columbia, and that's technically a rainforest, and we've been having terrible fire seasons for the past decade.

And so I saw it creeping northward up into Oregon, up into Washington, up into B.C., and so logically, you'd think, "Okay, this is still moving."

And I think in the Northeast, where I grew up, you know, a very familiar landscape to me, we've had this sort of sense, "Well, we won't be touched by that."

You know, that's a Western thing, it's an Australian thing, but we're nice and wet here, it's cool and green, and yet this trend in heating, warming, and drying across the continent is spreading steadily and measurably.

If you talk to foresters, if you talk to forest hydrologists, they have the inside scoop on that.

And so they're not surprised by this, but the United States right now is in the driest year in recorded drought history for the entire country.

- Help our audience distinguish in their minds what might be weather versus what might be climate, right?

'Cause right now, as we're having this conversation, I'm doing this from New York City, and we just experienced one of the longest dry spells.

We're starting to see all of this from this kind of month and a half, say, without rain.

But help us put that into perspective, that it's maybe not just this year or this cycle, what are the longer trend lines?

- So there are these kind of two tracks that we're on, and one is natural climate fluctuation.

You have warm years and cold years, you have snowy winters, you have dry winters, but then you also have, and so that's natural to see fluctuation there.

On top of that, though, we have fossil fuel emission-driven climate change, which is measurably heating the atmosphere and the oceans, and so that is this extra push from behind.

And so what we're seeing now is record temperatures.

It's certainly warmer than normal in the Northeast.

And think about your laundry outside on a warmer day.

Your laundry's gonna dry faster.

Well, so is the forest floor, so are the grasses.

But the other thing, when you look at it globally, it's not just the Northeast that has low reservoirs.

The McKenzie River, one of the great rivers of the Canadian North, is right now at record low levels.

There are huge lakes in the Canadian subarctic, really inland seas that are at record low levels.

The Amazon River is at a record low level.

So this is a global issue, and when you have warmer air, you're gonna have more evaporation.

What is so unseasonable about this?

What is it, you know, about this that is so out of the ordinary that even our bodies feel like there's something off?

I know I grew up in Massachusetts, and I remember snow flurries in October.

And I sound like an old man saying that, but I don't think anybody of any age remembers mass, you know, hundreds of wildfires burning up and down the I-95 corridor.

You know, that is not anybody's diary, you know, from the past.

And so we really are going through this visible, measurable change, and we're feeling it in our bodies.

It's changing our concept of what the seasons are.

And so now out West, people's concept of summer, rather than being this time of kind of liberty and freedom and being outside in the sun and the warmth, is when's the smoke gonna roll in?

You know, when am I gonna have to stay inside because it's too smoky?

And again, for, say, people in British Columbia or Washington State, that is just not a reality that any of us grew up with.

And so we're--you know, our consciousness is being sort of forced into this new concept of what seasons even mean, and that creates a real dissonance.

I mean, if you think about it, you know, we've been around for a long time, not just in North America, but, you know, as Homo sapiens on Earth, we've never had to go through a change this rapid, where, you know, in a decade or two, we're actually having to almost redefine what seasons are.

You wrote a fascinating book called "Fire Weather," and in it, you describe-- you go into the fire that was in 2016 in Alberta, Canada.

But one of the things that you mention in there is that essentially now fires are burning over longer seasons and with greater intensity than any other time in human history.

I mean, why is that?

- All right, there are a couple of factors, and one of them, you know, the simplest one is the heat that we're generating.

So, I mean, what the irony is, that our economy, our civilization, is powered by fire.

We think about oil and gas as energy, but it does not become energy until we burn it.

So we are burning literally trillions of fires around the globe in our engines, in our furnaces, in our hot water heaters, in our stoves.

Globally, there's a huge amount of fire and also emissions coming off of all of those fires.

So that's impacted the atmosphere in terms of CO2 and methane, making the whole planet hotter.

And the irony is that makes the planet more conducive to burning.

And so you couple that then with 100 years of very successful fire suppression, especially in North America.

So now you have these huge buildups in the forest, including, you know, in the Northeast, which, you know, was logged off 150 years ago.

There's a lot more forest there now.

But with these elevated temperatures, and more evaporation, you have drier forest, and it's easier for fires to get going.

And so in Fort McMurray, the petroleum hub of Canada, which is 600 miles north of the Montana border in the subarctic, it was 93 degrees.

There was still ice on the lakes.

It was 93 degrees.

And the relative humidity that day, May 3rd, 2016, was 12%, which is equivalent to Death Valley in the month of July.

And so we're having these conditions that create opportunities for fire that we've really hardly ever seen before.

- There were, in the fire that you're talking about, 88,000 people that were evacuated, right?

And when you see images of fire approaching different communities, especially in the United States, you see this sort of mix of reactions.

Some people are like, "I can't wait to get out.

"Oh my gosh, I'm stuck in traffic.

"This is horrible.

I don't wanna die here," right?

And then there's other people, similar to a hurricane, who end up trying to hunker down and trying to say, "This is my really, "really precious home, whatever.

"I'm gonna stand here with a fire hose."

What explains how this affects people in figuring out their kind of personal relationship to fire, the environment, their belongings?

- All right, this, I really think this is sort of the question for our decade.

You know, it's one of the big questions.

As fire impinges on our communities more intensely, 'cause it burns faster and more intensely now because of heat, and the journal, in fact, made that their cover story, of the changing nature of wildfire and how fast it moves.

And so many people who live in fire-prone places, especially out West, have a kind of outdated notion of fire and what they might do to combat it.

And now, fires are moving faster and with such intensity, so they can project radiant heat of close to 1,000 degrees.

You know, a human can't survive that.

But what if your home is uninsured?

Or what if you live on a ranch, and, you know, your grandfather fought fires, and your mom fought fires, and so you're going to, too, except now it's 110 degrees, and the relative humidity is in the single digits.

And so this fire is now-- it's not just going to be a fire on the land, it's going to be a firestorm rolling over you.

And yet there's this, you know, I think there's a natural stubbornness and wish to protect what's ours, but again, if you don't have the means to replace it, if you don't have insurance, which fewer and fewer Americans have now, that's going to change your calculus.

So there's a few different factors, but some of it, too, is, again, going back to consciousness and thinking about how we're needing to catch up with the climate.

The climate's moving beyond us right now.

We still have outdated notions of it, and it's capable of new outrages now.

We've seen it in the flooding, you know, after Hurricane Helen, and we've seen it in the fires in Paradise and Lahaina.

Really shocking energy.

I wonder why has it taken so long for the capital markets, the insurance providers, to reflect these kind of climate realities?

I mean, we see now there are a number of states where I think 12 insurance, 7 out of the 12 insurance carriers pulled out of California just in the last couple of years because they don't want to be insuring wildfires.

I wonder, like, why haven't the capital markets reflected this risk appropriately?

There is extraordinary dissonance in the financial sector.

And so where you have the insurance industry, who does the math, and they realize we cannot afford these losses anymore, I understand that 50 insurance companies have pulled out of Louisiana and Florida alone in the past four years.

I didn't even know there were 50 insurance companies there.

And they've realized they can no longer afford to cover losses on multibillion-dollar disasters, which are happening almost annually now.

So the insurance industry, in a way, is sort of the grown-ups in the room who are actually observing the damage done and tabulating it in this quite objective way.

Meanwhile, you have the petroleum industry and financial markets who are very bullish on anything that appears to make money.

And so there's a lot of investment in offshore drilling right now.

So there's this terrible disconnect and really conflict of interest, even within the financial markets.

And so that's another reckoning for the 2020s, that we're going to have to square up, or nature is going to square it up for us.

At the moment, the nominations that President-elect Trump has for his pick for EPA chief is Congressman Lee Zeldin.

He's got a fossil fuel executive who might run other parts of the division.

And I wonder-- and he's made no secret about wanting to withdraw from the Paris Accords, as he did the first time.

What does that do to any kind of cohesive policy?

Hari, it puts us in a really vulnerable position.

When you effectively have a policy of climate denial, which the province of Alberta does, and which it looks like the Trump administration may have-- so when you have the leaders saying, "This isn't happening, this is not an issue, "and yet we're having billion-dollar disasters "that are uninsurable every year, "we're having bigger fires, bigger floods."

And so there is, you know, we can't really function as a society in a world that is living by two different realities and two different standards.

And so with that-- I mean, the upshot for the citizen is suffering and confusion.

And the upshot for the states is they're going to have to take more individual responsibility at the municipal level, at the state level, for managing their own climate policy when, in fact, the science is objective.

What does that scenario look like as the map becomes less inhabitable for different climate reasons?

Exactly where do you go?

There's a kind of contraction that's going to happen, and it's going to be driven by the insurance industry.

And some people will still-- will remain without insurance, but you're really exposed, and that's a kind of vulnerability that makes it hard for societies to function well.

And this representative-- I think Senator Sheldon Whitehouse from Rhode Island put it really well when he said, you know, without insurance-- well, climate disruption makes places-- makes homes uninsurable.

And when a house is uninsurable, it's really hard to get a mortgage.

And without a mortgage, that impacts the housing industry.

And without a functioning housing industry, you don't have a functioning economy, because that's one of the pillars of the American economy.

And so it's not rocket science.

You know, it's really quite simple that when you put people in these vulnerable situations, when you don't deal with climate, don't deal with CO2, and the world becomes more flammable, more floodable, that is going to have direct impacts, measurable impacts, as we're seeing in the insurance industry, on our entire economy.

And so it really seems like good business sense to address climate in a meaningful way, which we have absolutely the tools to do.

- Is the global community able to get its arms around this?

I mean, because we seem to have these COP meetings increasingly in states whose primary economic driver is the fossil fuel industry, right?

This time it's in Azerbaijan.

It was in Qatar before.

And I wonder, you know, there are efforts to try to create funds to mitigate climate disasters, but it always gets hung up on, well, who's going to pay for it and how much are the, you know, the smaller countries who might actually feel a greater brunt of it just by their geography.

How much do they, how much are they entitled to?

How much do the people who are generating the fossil fuel emissions owe?

- There is no mitigation fund that's going to cover the global climate damage bill.

You know, when you lose an entire island, when you lose an entire neighborhood, my understanding for the, even just for Hurricane Helene, which is just one hurricane, I think that the tab for that is over $150 billion.

And then Milton, right on the heels of that, you know, that's right up there too.

No one even talks about Hurricane John, which came in at the same time and trashed the resort city of Acapulco for the second time in 11 months.

So that's a whole tourist city.

That's a whole economy basically wiped out.

Who's going to build there now?

So, you know, these hundreds of millions that people are talking about are drops in the bucket that's really going to be tens of trillions.

And again, that just highlights the dissonance, the kind of, there's a deep longing we have to maintain the status quo and that uneven transition into renewable energy, which is happening in parallel with these other things we've been speaking about.

It's underway.

I feel confident that it's unstoppable, but it's a patchwork effort at the moment.

- The book is called "Fire Weather," author John Valliant.

Thanks so much for joining us.

- Hari, great to be with you.

- And finally on that note, to save our planet, hundreds of climate activists gathered in Busan, South Korea to show us that life in plastic is not fantastic.

Forming a giant human sign urging end plastic.

They're calling for meaningful change to come out of United Nations plastic talks, which begin there today.

Many hope to see an end to our dependency on plastics to protect our land and our oceans.

Their continued activism, a barometer of how citizens plan to keep up the good fight for a better, cleaner future.

And that's it for our program tonight.

If you want to find out what's coming up every night, sign up for our newsletter at pbs.org/amanpour.

Thanks for watching and goodbye from London.

Support for PBS provided by: