On Camera

Episode 1 | 55m 14sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Meet some of music photography's greatest names as we define what makes an iconic image.

What defines an iconic image? This question provides the central theme for Episode 1 as we are introduced to some of music photography's greatest names.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionAD

On Camera

Episode 1 | 55m 14sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

What defines an iconic image? This question provides the central theme for Episode 1 as we are introduced to some of music photography's greatest names.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADHow to Watch Icon: Music Through the Lens

Icon: Music Through the Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipWhen you're young, you're told you have to have a job.

So I don't know, I'll be a music photographer, just because I can't think of anything.

There's nothing that would be better, and there is nothing that's better.

[rock music playing] A music photographer is the real key to the idealism and mystery that is the inspiring part of music.

I feel like I'm documenting musical history.

Getting to live it, up close and personal, it doesn't get any better than that.

I would never say I was part of the band, but I was connecting.

What I do is a form of music.

It's just music for your eyes.

Music photography is like the music itself.

It's part of our cultural heritage.

It's part of our shared identity as a people.

An iconic photograph is indelible.

It always stays with you.

Besides the music itself, these photographs are the most important visual document of these musical artists.

This is a collaboration between the photographer, and the artist and the viewer, and we're all willing it on.

We all want to celebrate this stuff.

That eureka moment.

That's it, I've got it and stuff.

So capturing that moment, it's like, wow, this is gold.

One millisecond later you haven't got it and one millisecond before you haven't got it.

But right on it, you've got it.

[shutter clicks] [theme music playing] ['No One Knows' by Queens of the Stone Age] What makes a great iconic music photograph is something that speaks to your soul.

♪ We get some rules to follow ♪ ♪ That and this, these and those ♪ What you're looking for as a photographer is to create the iconic picture that everyone knows.

[song continues playing] You can't really try to shoot an iconic photograph.

You can just hope that you're in the place in the moment, and you capture it.

♪ How they stick in your throat ♪ It's the artist, often at the peak of their creativity, caught really well by somebody who knows what they're doing.

♪ Oh, what you do to me ♪ I'm aiming for that piece of magic that bit of something that takes it to another level.

DAVID CLINCH: You got to figure out your own style.

What's it going to be?

What's your style?

['No One Knows' continues playing] My goal is to try to get deeper, to get deeper into a moment between myself and this musician and the collaboration that maybe, hopefully, they haven't given someone else.

Good art elicits a reaction and nothing more.

If it makes you move, babe, it's art.

There definitely have been times when I've taken a photograph and a shiver goes up your spine, and I thought, wow, this is it.

The hair stands up on the back of your neck, like I know this is a good shot.

I realize how special moments in time are.

It's actually why I love photography.

[music playing] The moment is the moment, and that's it.

JESSE FROHMNA: When I take a picture, I don't think of what will become iconic or if it is iconic.

Like a fine wine, it happens over time.

[music playing] A picture just becomes iconic, and that is almost despite you, not because of you.

There's pictures you take at the time there seems nothing, but when you look back at them 30 years later are really important.

[music playing] It's when you catch them at that moment that it just goes, wow, that's Diana Ross.

That's the great thing about music photography, it just captures the sense of the time and the zeitgeist.

['No One Knows' continues playing] ♪ Heaven smiles ♪ You have the opportunity to do legendary work, which should never will be forgotten.

That's kind of wow.

Some would say it's "much easier now" because you can "shoot in these bursts," but they're wrong, because that's like sifting through your favorite needle in a stack of needles.

It really is about a really great photographer identifying, in this preternatural way, like I'm near a moment and it's about to happen.

[snaps fingers] KEVIN WESTENBERG: The big question then is, how does an image become iconic?

How does it fit into society, into pop culture, into the grand scheme of things, and rise above what other people have done?

It's super difficult to get all those elements right.

[shutter clicks] [music playing] David Bailey's 1965 portrait of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, for me, that's photographic ground zero.

I saw that in a book in a school library when I was about 14 years old.

Until that point, photography was nothing more than family portraits and weddings.

That was the only reason that photography needed to exist.

And then I got in the school library one day, on a rainy lunchtime, and I opened this book, and there was this picture, and it literally just knocked me off my chair.

And I realized, oh my god, photography doesn't have to be like sitting in a high street studio with your mom.

Photography can be this.

This is what photography can be.

It's just a beautiful, beautiful distillation of the austerity of the image.

In my mind, that picture is the photographic equivalent of three-chord rock and roll.

That is A, D, and E in visual form.

Shadow, highlight, white background.

That is A, D, and E, right there.

That's Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis.

That's Louie Louie.

It's all of it in one picture.

[music playing] I think magic happens.

I really believe in magic in photography.

Things happen, and you go, how did that just fall into place?

[grunge music playing] JESSE FROHAM: Kurt Cobain showed up four hours late, and we had a definite schedule.

We had to be finished by a certain time.

So what was expected to be a five-hour shoot turned out to be a 30-minute shoot.

Many shoots you have to roll with the punches.

I mean, that's just the way it is in our business of music photography.

But when he showed up, he was so stoned that he honestly was like Silly Putty in my hand.

[song continues playing] He showed up, oddly enough, with a bag of clothes, just stuck under his arm.

And he asked me if I had a bucket.

That was the first thing he said.

I said, of course.

We can get a bucket.

What do you need a bucket for?

He said, I think I'm going to puke.

I mean, we had planned to do a five-hour shoot on location and had people waiting in Central Park in New York City and on the streets.

When I arrived with a production crew, I was told we had to shoot in the basement of a hotel room.

I don't shoot very quickly because I'm a controlled studio photographer.

He's not a model who's doing 1,001 poses, so you have to take your time and be patient with people in the studio.

So because you don't have the environment to work off, it's a limited arrangement of tools you can use.

It's a plain background and light, basically.

When I got the film back from the lab, I knew I had something really special.

[grunge music playing] It really was fate because I don't think I would have had anything close to this kind of an image of him if I had shot on the streets.

[grunge song ends] ['Voodoo Child' I photographed Jimi Hendrix early in '67.

And I met him soon after he arrived in London in '66.

♪ Well, I stand up next to a mountain ♪ ♪ And I chop it down with the edge of my hand ♪ He was playing in a small club, being launched to the media and to the music business.

And his music went right over my head.

I didn't get it.

I thought it was raucous, I thought it was rather tuneless.

♪ 'Cause I'm a voodoo child ♪ ♪ Lord knows I'm a voodoo child, baby ♪ But what I could see was that this was an extraordinary, dynamic, charismatic individual doing the most amazing things with the guitar, and I knew that I wanted to photograph that.

[guitar solo] I wanted to capture the real person.

That was what interested me.

And I thought the way to do that was to take what I considered to be a serious proper portrait, which meant black and white.

And I wanted to give him gravitas and dignity.

I wanted to treat him as a serious musician.

And he gave me this extraordinary series of moments.

[rock music playing] JOHN VARVATOS: Gered's picture of Jimi Hendrix from Mason Yards is one of the most iconic pictures in history.

And it's Jimi.

It's the way it was shot.

It's the lighting.

It's all the things that came together as magic.

I've been looking at that picture from the time I was 12 years old and I never get tired of it.

[rock music playing] GERED MANKOWITZ: He didn't have any sort of mask.

He was exactly what you see is what you get.

There was no styling.

He wore the clothes that he liked, which included the military jackets and a police cloak and beautiful Victorian, Edwardian shirts and velvet and lace and silk.

And he just looked absolutely fantastic.

He didn't try particularly hard.

He responded to my minimal direction.

He just looked into the camera and he let me in.

It was absolutely fantastic.

[rock music continues] JILL FURMANOVSKY: Hendrix knew that Gered and him would be able to produce something together that was going to be iconic.

Now, he may not have thought of it in that way, but Hendrix is giving Gered pictures.

There's something going on between the photographer and the artist in those pictures.

GERED MANKOWITZ: I knew at the time that I was grading great pictures, but I had no idea that he was even going to be successful.

No idea that he was going to become such a huge star.

And of course, no idea that he was going to be dead within three years.

[light electric guitar playing] DAVID FAHEY: You can't escape that penetrating gaze and that strength that this musician has.

I mean, it's the prime of his life.

He's direct, forceful.

You know the music behind that face.

It says it all in one image.

That was the only one I shot on that roll like that.

All the rest of the pictures on that roll have the band with him.

I don't know why I got rid of the band and I asked him to do that, and I don't know why I didn't shoot 10 rolls like that.

But I didn't, and that extraordinary picture that has a life and an energy all of its own is the only frame in that whole session like that.

[music concludes] If you're going to start with the rock and roll tradition and what music is going to become, you've got to go with the blues.

And if you're going to go with the blues, you've got to go to Robert Johnson.

['Sweet Home Chicago' by Robert Johnson] ♪ Baby don't you want to go ♪ ASHLEY KAHN: That's an amazing historical shot.

GERED MANKOWITZ: He's sitting down in a photographic studio.

It was the Hooks Brothers Studios in Memphis, Tennessee, about 1935.

He's dressed in his Sunday finest.

And it's just a photograph that is old-fashioned and modern.

Everybody knows that picture in music.

It's just a telling picture.

It looks like this stylish, flashy guy that really knows what he's doing.

SEASICK STEVE: When I saw that picture of Robert, man, he looking good, and knowing it, too.

Looking like a ladies' man, and all his music is nothing but sexy.

History was made by finding an image of this legendary and important figure who sold his soul to the devil.

♪ Land of California to my sweet home Chicago ♪ The idea of a man going down to the crossroads, selling his soul to the devil in a Faustian pact, and then returning with these sublime skills as a guitar player is just this thing that inflames the imagination.

ASHLEY KAHM: It was amazing how rapid his musical ascent was.

He went from being someone who was just stumbling around on a guitar to becoming a poet on the level of Bob Dylan.

That music was the genesis of everything that we know as rock and roll.

That photograph, for a Black man in the 1930s, was more polished, more sophisticated than any White American would expect a rural sharecropper to be able to achieve, and it predicts the kind of ambition and aspiration that's going to be in hip hop covers in the '80s and '90s.

That's the image that really kicked off this whole idea of iconic music photography.

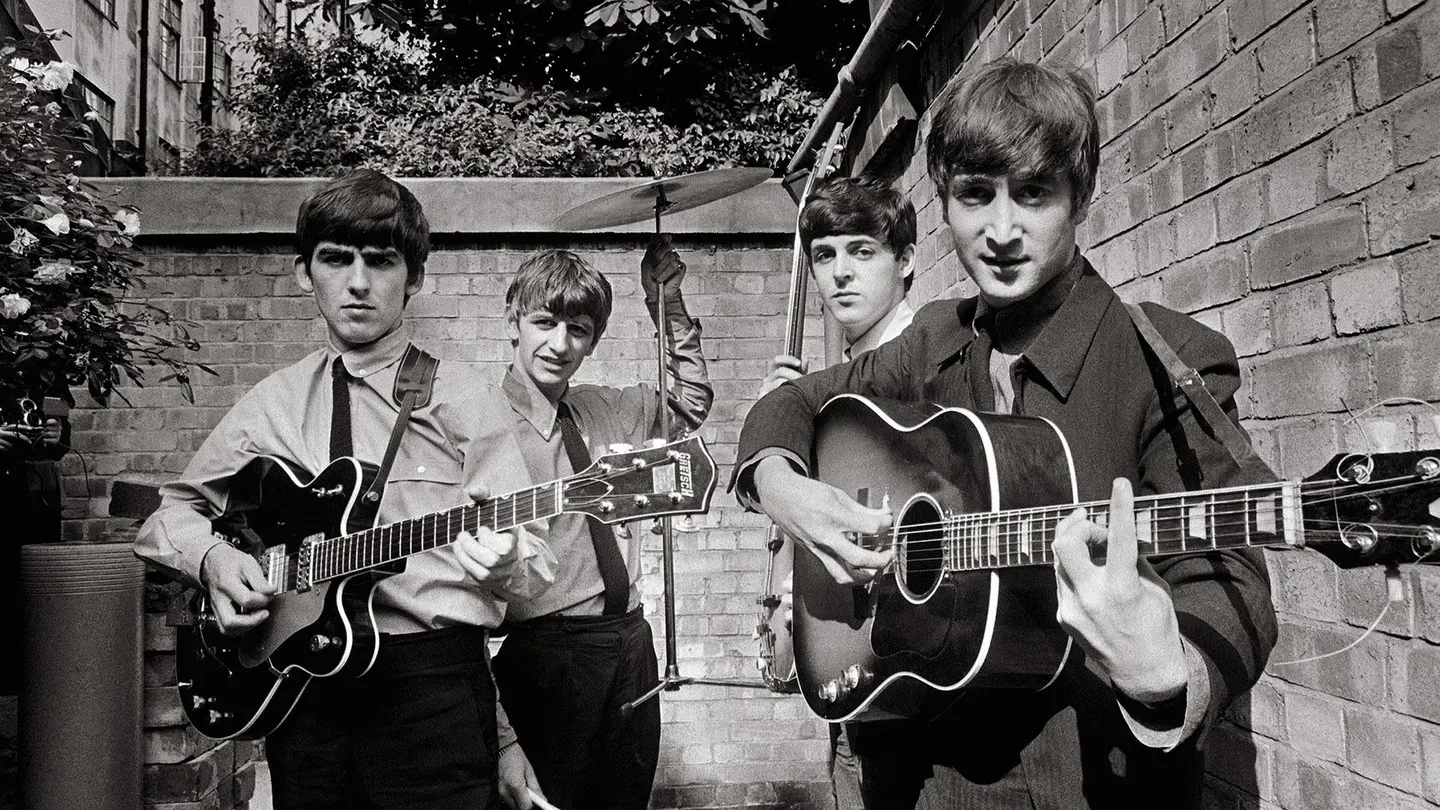

[old-time guitar playing] [rock music playing] I was working at the Daily Sketch and I told the picture editor on the Sketch, I said I didn't really know what I was doing.

He said, don't worry.

I'll look after you.

He said, I'm really employing you because you're a musician, and we think pop music's going to be big in the '60s, and we need someone young, their age, to communicate with them.

So he said, you start Monday.

And he said, I want you to go down tomorrow to Abbey Road.

There's a group there called The Beatles and they recorded something called "Please Please Me."

Go down and photograph them, and I did.

[rock music playing] John had the best personality so I put him in the front.

Paul was the next one.

George was the nice guy.

And so was Ringo, but I had Ringo holding the cymbal.

I mean, it was a joke, really.

[music playing] Anyway, the picture published.

The papers sold out so that we did write about the success of pop music.

And I go in the next day and the phone rings.

It's Andrew Oldham.

And he says, I'm the manager of The Stones He said, can you do for The Stones what you did for The Beatles?

So I went and photographed them.

So I started at the top and never looked back.

I mean, none of us knew what we were doing.

I mean, it was all brand new to all of us.

I mean you couldn't believe that you get paid to do exactly what you wanted to do.

[rock music playing] We used to go to a club called the Ad Lib Club.

The Beatles and Stones, we used to sit and we used to talk about what job were we going to get when all this was over.

We were all convinced it was going to be over in a couple of years and we're going to have to get a proper job.

[rock music continues] I remember photographing The Stones and people would say, what was it like?

And I said, they were the youngest band I've ever shot in my life, because all they were was full of energy.

[music playing] They're a gift.

You know, when you get to photograph people like The Stones, they're a gift.

They totally understand the-- the game.

They know exactly what to give you.

They know their angles.

They're like four times Kate Moss, they're like-- always fags in their mouth.

Even now they're all like that, like it's bizarre.

And they look good in anything.

You could put them in a plastic bag and they look good, so they're just a gift to you.

And I think the main thing for me when I'm shooting them is to just let them be themselves and to encourage that.

GARED MANKOWITZ: In my experience, some of the most rewarding and satisfying sessions have been with artists early on in their career, because there is a willingness.

There's an innocence.

There's a naïveté.

They want to create a great image.

And I love that.

[music playing] JANETTE BECKMAN: When you're photographing these bands in the early stages of their career, they're just getting their image together.

[hip hop music playing] Like Run-DMC in 1984, on the street where they live in Hollis Queens.

They had this attitude and they knew how to pose.

And, you know, I'm looking at them.

I get that picture maybe in the first 12 shot roll.

That's a tricky picture because there's a lot of dappled sunlight and you've got black faces, white Adidas.

You know, they've got Cazals, Kangol, and they just look so damn cool.

They weren't that big.

In New York people knew of them.

Then they became one of the hugest hip hop groups to ever walk the face of the earth.

DAVID FAHEY: People like the beginnings because it's when they were blossoming.

That's when there were fresh.

How did it all start?

What do they look like when it started?

Where they are young and sexy?

Were they quirky?

What really made them look appealing?

['Everybody' by Madonna] ♪ Everybody, come on ♪ ♪ Dance and sing ♪ ♪ Everybody, get up and do your thing ♪ ♪ Everybody, come on, dance and sing ♪ ♪ Everybody, get up and do your thing ♪ There was just something so intoxicating about this woman.

♪ Find a groove and let yourself go ♪ ♪ When the room begins to sway ♪ DEBORAH FEINGOLD: One was taken with her.

She had a really strong presence.

But, you know, it was interesting.

She was ready and I was ready, and that is exactly what the shoot was.

We both got to work.

♪ Everybody, you can do your thing ♪ ♪ Everybody, come on ♪ It was completely set up before she came in.

It was a little 500-square foot room that I lived in.

So the dining room table folded back.

The bed was a futon that folded back.

And I set a 9-foot wide seamless at one end, and that's as wide as the room was.

And then we rolled it out.

And we had one front light and then a light behind her.

There was clearly no catering budget, but I had a bowl of bubblegum and lollipops.

I'm not sure why, but that was the food for the day.

[pop music playing] We shot four rolls of film.

But it was a Hasselblad, 12 exposures, so maybe 48 pictures, maybe less.

I didn't direct her at all, except to say, could you move a little this way because she was covering a light, which was very distracting for me, and yet it's that glow behind her that really makes it from a flat image to one with some depth to it.

The lollipop image, there is an innocence to it.

I didn't ask her to hold it.

Can you imagine me telling her how to pose?

God.

[laughs] But she must have picked it up.

I-- I can't imagine me saying, oh, could you be seductive with that lollipop?

[laughs] It was really her show.

But here-- here's the thing.

I can't imagine that that entire shoot took more than 20 minutes.

She was so confident in who she was, and what she was doing that it was just the dance and she led.

[pop music ends] ANDY EARL: Madonna's one of the best people to photograph in the world.

She walked in and went, I chose you because it looks like you make people laugh.

It's nerve-racking when people say that to you, but that is kind of what I am.

I never, ever worry about being a twat or being an idiot.

I've got no fear of that.

A lot of my pictures seem improvised, but have a little bit of the performance element to them, you know.

The fist thing I go to.

It's like give me-- give me the fist.

Give me the fist.

I get people to scream.

I scream at people.

You're there to create an image.

I mean, some bands give it to the photographer and, you know, some photographers push that out of them and some photographers seduce it out of them.

Some of the best photo shoots that I've enjoyed is when you're just having a conversation and the photographers taking pictures while you're having that conversation.

You didn't even know that you're actually having a- a photoshoot.

And all of a sudden, it's like, we're done.

Most people hate having their picture taken at the end of the day, and so you're trying to make the process fun because if it's fun for them, you have their confidence.

JONATHAN MANNION: It's never about imposing your will, but it is having a strong position that can then either be challenged or played into.

You got to remember that there's an aesthetic that goes with being in a band, or being on stage.

And they can't see it so, they're really looking to you to give them that.

I never particularly enjoyed having my photo taken, but when the result is something that is quite iconic or powerful, then you kind of think, well, that was worth it.

Me, what I do is performance.

I have to encourage that person to be comfortable and to be who they are, and to be relaxed enough with me to become themselves, let themselves out.

You've got to get those people in a place where they forget why they're there, because that's when everything slides and slips.

But that's when you get the magic.

There's a beautiful sweet spot that you can find when you're looking down the lens.

You can't lie.

You can't use your wizardry with your words.

People can see and they can feel.

And I think that the photographers out there who know how to make you feel easy, they'll catch that moment.

[acoustic guitar playing] BOB GRUEN: '71 was the first time I saw John and Yoko at the Apollo Theater, and I took some pictures of them backstage.

There were several people taking pictures while they were waiting for the limo.

And John looked around and said, people are always taking pictures of us like this and we never see them.

What happens to these pictures?

And I said, I live around the corner from you.

I'll show you my pictures.

And he goes, you live around the corner?

Slip them under the door.

As I started working with them, Yoko said, we're not going to pay you, but you'll get great access to have pictures that you'll be able to make money selling to the public, if you'll show us the pictures and use the pictures that we like.

[mello rock music playing] I started going to the studio and hanging out with them.

We had a lot in common.

We had the same cynical kind of sense of humor, outlook towards the world.

We were both drinking a lot.

And one night when I was on my way to see John, I was going through Times Square and I saw the guys selling the T-shirts.

I thought, oh, I'll get one for John.

So I picked one up, cut the sleeves off with my book knife, and I gave it to him that night.

And it was a year later on his rooftop-- he had had a shower.

His hair looked good.

And so we started taking some pictures of him sitting on the ledge and at different places around the roof.

And then I said, do you still have that New York T-shirt?

Would you wear that?

We got the skyline.

It's perfect.

We're here in New York.

Wear the New York shirt.

A lot of people in New York come from somewhere and end up staying here, and I felt he was going to be a New Yorker.

New York's an attitude.

He wasn't saying I'm a New Yorker.

He was saying New York.

You know?

There's something about that.

You just know what he's talking about.

You know that it's that power.

It's that peak.

It's that perfection.

It's the ultimate.

JULIAN LENNON: People looked at him differently over there.

He crawled out of a caterpillar of life in The Beatles years and this was one of his butterflies.

BOB GRUEN: Two of the pictures from that one roll were both very popular, the one with the New York City T-shirt, that's the most well known.

And there's another one where he's got the denim jacket on that's equally comfortable, and powerful and available.

There's something about the picture that although he's got the sunglasses and he's a pop star and looks cool, he's very available.

He's very open.

He looks like he's about to have a conversation with you.

JULIAN LENNON: You could see that Dad was completely comfortable with Bob.

You can see that there's mutual respect in that relationship, and that's why I think that most people who look at that image can feel a part of, it because it's Dad chilling out and relaxing and having fun.

[rock song ends] I'm a big fan of capturing a moment.

I like to be loose and free and shooting what's in front of me.

You know, I just really enjoy the photograph as a document.

I have been photographing all the winners and performers at the Grammys for like 15 years, right?

At the end of the show, all the artists come back, especially the more famous artists.

And they won't stand in line for long, but there does-- a line starts to form.

And you're shooting, and I happen to be photographing BB King.

And I'm a big blues fan and I had worked with BB King before.

And we were shooting and I was getting into it.

And I could tell that everybody around me who's normally looking at, say, my subject, they're looking behind me and they're not looking at BB King.

So I kind of turn around and I look behind me and there's Paul McCartney and like Dave Grohl and Jay-Z.

And I don't want to rush BB King because he's one of my heroes and certainly I want to get the great photo.

And I turned to Paul McCartney and I say, um, Paul, uh, I want you to know, just let me finish with Mr. King and then I'll bring you in.

Of course, you've met BB King before, yeah?

And Paul says, actually I've never met BB King.

And so I said, oh, well, allow me.

And I walked him over.

Paul McCartney, meet BB King.

[blues music playing] I whipped out my camera and got a shot of the two of them just admiring each other, and it was pretty cool.

NEAL X: Being a photographer was super, super cool in the '60s and '70s.

They had to recognize who was going to be interesting, get in there, and capture the right stuff.

It's not about the equipment or anything.

It's about being there and realizing you had a moment to capture.

Without that, there wouldn't be any great iconic images.

['It's All Over Now, Baby Blue' by Bob Dylan] Just get Dylan to be your subject and you're halfway there.

♪ The highway is for gamblers ♪ ♪ Better use your sense ♪ ♪ Take what you have gathered from coincidence ♪ ♪ The empty-handed painter from your streets ♪ ♪ Is drawing crazy patterns on your sheets ♪ ♪ The sky, too, is folding over you ♪ ♪ And it's all over now, Baby Blue ♪ I was given, uh, a special setting for about 10, 15 minutes with him, but we just hit it off.

[Dylan music playing] I wanted that first session to be really good.

When you're in a recording studio with all that equipment, they all look somewhat the same.

You have to find your moments.

And, uh, they liked what I had done, and then I felt, OK, now is the time to move.

Would you come to my studio?

In the photo studio, you have lots of props and all that.

I'd give him something and he'd do something.

I'd give him a little painting that I had used in some photograph a week ago.

I gave it to him and he'd take it and he'd blow smoke in her face, things like that.

Basically, if you have any sort of rapport with him, you'll get a picture.

Because he really goes for it.

He really thinks-- he thinks very quickly.

He'll come up with something, and if you're fast enough, you'll catch it.

If I throw him my keys, he would take it and he would do something bizarre, which I wouldn't have done if somebody threw me the keys.

You know, so he had his own special ways.

And if you go through the, uh, contacts, you'll see different things that he would do.

Even one of my favorite photographs of Dylan where he covers his face.

I took it.

I didn't ask him to cover his face.

When I see it, I take it.

His manager liked the photographs I was taking.

Albert Grossman said, would you like to do a cover for us?

I said, uh, I'd love to.

And, uh, he told me it's called "Blonde on Blonde."

I still don't know why it's called "Blonde on Blonde."

I don't know if anybody else does.

Most of the studio thinks we're-- we're pretty good.

You know, but halfway through the sitting, I just didn't feel I was getting something special.

So I said, uh, would you go out with me?

I want to go out in the street.

He said, yeah, OK. Let's go.

[Dylan music playing] I knew that I wasn't holding it as steady as I would like to.

And I tried.

I held it.

But there were five, six, eight images that were blurred and moving.

And, uh, when I got them back, I immediately put them on the side.

I figured I won't send it to the record company.

They're not going to put on a photograph that's moving or blurred.

And he-- while going through them, he said, what's that?

When he saw that and I told him, he said, that's the one I want.

[Dylan music playing] There's an image right after it, where he has a slight smile.

And the one that we chose finally doesn't have that smile.

That's a major difference for me.

People started to say, what is-- what is the interpretation?

Is that you're trying to show a drug high or something like that?

I said, no.

It was cold.

It was February and we were both wearing light jackets and I tried to stay as straight as I could, you know.

I think the sleeve to "Blonde on Blonde" is a-- is a remarkable moment in time because it breaks all the rules.

The blurriness does define the music that is on that record, but also, it seems to say I just don't care.

You can think what you like about me.

I am me.

I'm just going to stroll on.

I loved it, but I put it aside because I figured the record company wouldn't go for it.

He said, no, no, no.

Let's go that one.

And what Dylan wants, Dylan gets.

I usually use the location as a cue to kind of get an idea.

With musicians, especially, they've got such a set idea of who they are and who they want to be and how they want to be portrayed.

I think as a photographer, to go in with a concept and say, I want you to do this, I think it's-- it's kind of disrespectful in a way.

I like to let them show me who they are, and then I-- it sounds pretentious, but I'm inspired by that.

[electronic music playing] Working with Billie Eilish for NME was interesting because it was a few days before her 17th birthday.

So I'm nearly double her age, and she's also like way cooler than I could ever hope to be, no matter how old I am.

She had a stylist.

And I went into the stylist and I was like, what colors are we working with?

Because the location was quite loud, color-wise, so I didn't want to clash too much.

And she was just like, Billie decides whatever she wants to wear.

She came in wearing kind of this weird Louis Vuitton brown velour tracksuit that I was like, it's an interesting look.

[pop music playing] She kind of swamps herself in her styling.

And the second look we did was this giant yellow fisherman coat by Montclair, so it probably cost thousands, and she could barely move in it.

At one point I had her sitting on the floor in it.

And I had to kind of like manhandle her down because she couldn't get down in this outfit, and then I had to manhandle it back up because she couldn't actually move in these clothes.

You just have to let her do her thing because she has a thing.

[electronic music playing] I've never seen anyone who is so naturally beautiful try hard not to be.

[electronic music playing] I had three hours with her so you've got more time to be like, OK, well, she's doing that, so how can I translate this into what I want?

[electronic music playing] It comes down to letting musicians be themselves.

Even if I don't agree with what their look is or what their aesthetic is, even if I don't really like it, it's not up to me to say, no, I want you to look like this because I want people to be who they are.

[music playing] ALBERT WATSON: Some people, it's easy to photograph them and they're used to being photographed.

Other times people are very shy and-- and very worried about the shooting.

So therefore, you really want to go above and beyond and spend that time.

If you've already got Michael Jackson, Kanye West, 50 Cent, Slick Rick, it doesn't matter.

I'm just very straightforward and honest with them.

[pop music playing] Beyoncé is really the nicest, sweetest person.

I did most of the photography with her when she was with Destiny's Child, and she was just wonderful.

She was friendly, very humble, very open to doing, uh, different pictures.

[pop music playing] She had a great outfit that I photographed her in, which was a kind of July the Fourth stars and stripes hot pants outfit with a little hat, you know which I loved.

[pop music playing] Did a body profile turning towards the camera.

And she looked at the pictures.

She says, oh, I love it.

And she said, can I just speak to you for a moment in private?

I said, sure.

So I looked at the Polaroids.

I kind of anticipated what she was going to say.

And I said, do you mean your backside?

She said, yes.

And I said, do not worry.

We can retouch that much smaller if you want.

Then she looked at me, gigantically horrified.

She said, smaller?

She said, I need bigger.

[electronic music playing] BOB GRUEN: You have to do your best to try to make the act look good.

You know, if you're on assignment you're just meeting somebody in a hotel room and you've got 10 minutes to take their picture, you still have to try to figure out who they are, what they're trying to say, and how best to express that in the picture.

Before I shoot, I'll do as much preparation as possible.

Come up with different scenarios, come up with-- even work out roughly what I'm going to do with the lighting.

So I go in there really, really well prepared.

But there's always a bit of luck.

[rock music playing] ANDY EARL: Morrissey was living in Los Angeles, and he's always had an obsession with James Dean.

So we thought, right.

We'll shoot him at the Griffith Observatory, which is in Los Angeles, and it's where they filmed "Rebel Without a Cause."

So we arranged that we're going to meet him there up at lunchtime.

I went up there and I wanted to shoot with a panoramic camera.

It's like vista division, a big, wide view.

And so I went up and we found the telescope, and it was a nice, little bit of graphics and things.

Got it all set up ready for lunchtime.

He didn't turn up.

2 o'clock, he didn't turn up.

Then it clouded over and it was all going a bit blah.

And he turned up at about 5 o'clock, you know.

Oh, sorry.

I'm a bit late.

And, uh, sat him down, started taking the photograph of him.

And because we'd lost all the light, I ended up putting a little flash, which gives a sort of shaft of light across his body.

And then suddenly, the whole thing had like a three dimensionality to it.

And actually, the stoney sky helped the feel of the picture, rather than it being a nice, pretty blue sky.

And it said "The Telescope" going one way and he looked the other way.

But the other thing was that when we then printed it up, looked at it, where he's actually sitting, somebody had scratched "soul," S-O-U-L, as in soul music, on the side.

So when he saw that, he thought that was great.

[rock music playing] Often, we can see this way, and when someone forces you to put a different vision on, it expands.

The Sinéad O'Connor assignment, we shot it in her hotel room and I asked my assistant to get the-- the lights set up.

And he basically said that would be a problem because he forgot the AC cord.

[laughs] Now, this shoot's going to happen now whether I have it or not.

So what photography taught me was how to improvise, and that is honestly how that shot happened.

[music playing] I had my tripod.

It's a very long exposure, and I wanted to blow the background out and just silhouette her.

Didn't really know-- remember, it's not digital.

I've got a Polaroid back, but I'm not really seeing exactly how it's going to look.

[music playing] That's why it's really exciting, as a photographer or a filmmaker or whatever, to always be open to that wasn't what I was going to do.

God knows I didn't know what I was going to do.

I was only shooting in her hotel room.

But I never would have seen that if that hadn't happened, and that's sort of what makes your career really interesting.

I think a good picture reflects the band and what they're about.

If they're a young, punky band, I want some spunk in the picture.

I want some character, I want some bollocks in the picture.

A soul singer, maybe the polar opposites.

[inaudible] said I want a huge spliff on the burn with them or something.

I want something to reflect what they're about, if you can.

That's not always there.

Those props aren't always there.

Then you strip it back down and you just want the simplest thing.

You want-- you want to show their character.

Want to show what they're about.

JONATHAN MANNION: I'm not always going to walk into a situation with a plan.

You know, if everything goes right today, I'm going to get A, B, C, D, E, F, G. And that's it, and those are my shots, and whatever.

And inevitably, in hip hop, people change their minds.

I did one for The Source with Snoop in Baton Rouge.

He had signed to No Limit Records, and quite literally, he showed up to get a check from No Limit.

And then he was like, oh, man.

I'll be right back.

I got to go pick my wife up from the airport, but I'm-- I'm going to come back.

I was like, Snoop, I've been waiting for you for three hours.

You're not coming back.

Give me a little burst.

Give me like 30 minutes, man.

And like let's see if I can even get it within that time.

That might be all I need.

And he's like, oh, but she's arriving and late.

And I was like, I could see that he was lying to my face.

I was like, dude, come on.

Let's do the dance.

Out 20 minutes.

He's like, ugh... six.

I was like, 18.

12.

And like, you know, we just sort of like landed at this thing.

I literally got 12 minutes with him on the side of a building.

I got 20 rolls of film, 10 sheets of 8 by 10, and a pack of Polaroids.

And he took off.

And I was like, thanks so much.

See you later.

And the images were fantastic.

[music playing] I love Snoop Dogg, and he's a [bleep] character.

Snoop is a wonderful subject.

I mean, in terms of West Coast hip hop, he's clearly our icon.

He is one of those characters that has been omnipresent throughout the entire journey, who, at the same time, is so accessible, so humble, yet has so much cultural significance.

I mean, he's a national treasure of the world, really, but certainly of hip hop.

[rap beat playing] TOM SHEENAN: He's implicated in a trial for murder.

And we knew we were going out there to do this piece and we knew that we couldn't talk about it.

[music playing] So I was in a cab to Heathrow, and there's a joke shop on the corner of Amen Corner in Tooting.

And I thought, I'll get some handcuffs.

So [inaudible] got them.

Went in, went to America.

So we go there, and there was like a party.

It was the end of the party, a weekend party, by the looks of it.

Off their bonks on chronic, I believe it might have been called.

Got the interview.

I said, well, let's go outside for some pictures.

I said, OK, do you remember the guy Smith at the Olympics, you know, giving the Black Power salute?

He goes, yeah, of course I do.

I said, could you repeat that?

He went, of course I can.

So he put his arm up and I clipped the bracelets on, and I just went [camera noise].

Hold on, bit of color.

[camera noise].

And that was it.

It just said it all.

Get it as fast as you can as good as you can and make it count.

And I'm quite proud of that shot.

That shot is shot inside an LA prison.

[laughs] I'm the only man who put Snoop Dogg inside a prison cell.

[laughter] The whole of LAPD tried all their life and never-- yeah.

OLAF HEINE: I didn't want to do the cliché hip hop picture, but I looked at his physics and at the shape of his face, and for some reason, I had this idea like he looks a little bit like Asian Huns, wise but also warriors.

So I told my stylist, bring a sword.

Bring the dress and everything.

So I started some other pictures to get warm with him, and then at some point I mentioned, do you know the Shaolin monks or the samurai, the wise warriors?

He's like, that's me.

Let's do it.

[rap music playing] The silhouette shot was the same session.

It was like after we did that picture where he were sitting at the table and he started like [sword noises].

And we were in this warehouse in downtown LA and he was in front of the window.

And I'm like, freeze.

Even if you don't have the details and it's all black and it's a silhouette shot, you can tell it's him, you know.

[rap music playing] JESSE FROHMAN: I think what made me a good photographer of rap was I was bringing to it something else that I felt other photographers weren't, and that was detail.

[music playing] Flavor Flav, he was like James Brown to me.

He even spoke like James Brown and had that raspy voice.

And, uh, he came over to my house and I could tell right away he was crazy.

Um, fun crazy, but crazy.

He would come out of the bathroom and say, yo, Flavor Flav flushed the toilet.

And like these strange things would come out of his mouth.

And I'm like, OK, he's going to be a fun one.

I took him up to the roof because the light was beautiful that day, and he sent my assistant out for white gloves, so almost like a mime act or something.

So he had these white gloves on, his dark skin, and he had a red tracksuit, I remember.

And he had this grill say Flavor Flav, the cutouts.

And I realized that even though he had this crazy energy, that I could describe everything I needed to describe about him by photographing his teeth.

And I went in as close as I could with my Hasselblad.

To get Flavor Flav to sit still for five seconds is almost impossible, and to have critical focus when you're in that close, photographing literally just this much of his face.

You know, I looked at the lighting and framed it just so, and that picture is now, to me, one of the most favorite pictures of all the rappers I've shot, and it doesn't even show his face.

[music playing] That said so much about hip hop to me that I knew, in some sense, it would become an iconic picture.

I have never really met anybody in a band ever that's like who they are in the media.

Bono, super excited.

Loves, loves, loves the whole thing.

Just loves everybody.

I photographed him recently.

He walked in and he shouted as he was walking in, don't you find that you miss someone even more just as you're about to see them?

Liam and Noel, again, Liam, especially.

Everyone's got him marked out as this tough guy.

He's just taking the mickey all the time.

CHALKIE DAVIES: People like Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney are very difficult to photograph because there's no picture that you can get, really, that hasn't been done.

Their faces are so incredibly well known, and so you have to have ideas.

OLAF HEINE: I look at the artists that I've photographed and most of them have been shot for millions of times, like U2 or like Sting, so I have to find my own little path.

And most of it has to do with what I feel when I listen to the music or when I talk to the guys, and then all of a sudden, from somewhere, there's an idea.

You don't know that you've got an iconic image until that image is being given a chance to grow.

It happens because the artist maybe dies at a young age and at the peak of their fame, as Kurt did and Jimi Hendrix and others.

They become iconic, and then the potential for their pictures to become iconic can happen.

GERED MANKOWITZ: The Jimi Hendrix picture didn't really become iconic until a long time after his death because it wasn't really seen very much.

I've always held my work back a lot, like I didn't want it to be oversaturated, you know.

And I think that worked against me because I think a lot of what makes certain photos iconic is just that everyone has seen them.

It's the viewer.

That's it.

That's what makes a photograph iconic.

It's how many individuals respond, have some emotional resonance with a particular image.

CHRIS MURRAY: I've sat with the same photo for 20 years, 30 years.

It reveals more to you if you're serious about looking at these things.

The subject dies, the photographer dies-- a lot of things can affect how you look at it.

[reggae music playing] ADRIAN BOOT: When I first photographed Bob Marley, I wasn't in awe of this superstar.

Nobody had a clue that he was going to be a superstar.

[music playing] The legend picture was an outtake.

It came from some photos I did of a video that was being shot at the Keskidee Centre in London, which is a community center, and there was a children's party there.

[music playing] It's not a particularly good photograph.

If I was judging a photographic contest and that picture came up, I would dismiss it on all sorts of grounds.

Technically, it's not brilliant.

It's available light, 800 ASA, Ektachrome.

It's not that good, really.

[laughs] Photographs can carry its own influence, its own message without the words, without the sound without the music because of what they know of this man in the photograph.

It's become iconic.

If you think of Bob Marley, you think of that image, or most people do.

Nobody had a clue how important Bob Marley was in those days, in those early days.

It wasn't really until after he died that he became as big as he is today.

[pop music playing] I've got two pictures of Bob Marley, one in the living room, one in the kitchen.

When you think of him, you only think of positivity.

It's like his image brings light to a room.

I like having a picture of my father.

It represents something to someone, and influences them, too.

Photos have the power of magic.

They're pigment on paper.

Those silver prints or those color prints, there's a magic in how that all comes together, and they're in front of you as this great artist, poet, what have you.

The whole idea of portrait photography is capturing something different, capturing something in their eyes, capturing something in their soul.

I'm rather on this side of the Native Americans who said you're going to steal the soul when you take a picture.

I'm stealing a little bit of that soul of that person in that moment.

[music playing] You can have a sense of communion with this person through these photos.

They actually have that sort of impact.

They move people, just like the music does.

[theme music playing]